For Israeli high-tech, 2021 was a ‘bumper’ year says head of Innovation Authority

In the face of the pandemic, soaring investments in capital and a new crop of unicorns, creating the ‘best year ever’ for the sector

Hanna Teib

Dror Bin

There aren’t too many people who would characterize 2021 as a “bumper” year for their field, but that is exactly the word that Dror Bin, CEO of the Israel Innovation Authority, uses to describe the country’s high-tech sector during the second year of a global pandemic that brought additional lockdowns, border closures and successive waves of virus variants.

“I don’t think anyone would have expected Israeli high-tech to peak in such a way,” Bin, who was appointed CEO of the authority a year ago, told The Circuit in a recent interview. “It was possibly the best year ever for Israeli high-tech.”

Bin’s decisive statement is backed up by staggering data collected by the authority, an independent public entity that works to bolster Israel’s innovation ecosystem and serves as a bridge to the government.

During 2021, Israeli companies raised more than $22 billion in capital; exits, mergers and acquisitions, and initial public offerings totaled $80 billion; the accumulated market capital of Israeli companies trading on Wall Street was $300 billion; and there was a record 79 unicorns, companies valued at $1 billion and up.

In addition, the IIA noted that Israel’s high-tech sector now accounts for some 50% of Israel’s total exports and for 15% of the country’s GDP. Ten percent of Israelis work in high-tech, paying some 25% of the country’s total income tax. National expenditure on civilian R&D stands at 4.9% of GDP, second only to Korea and ahead of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average of 2.47%. It also places third, after the U.S. and China, in the number of companies (116) listed on NASDAQ.

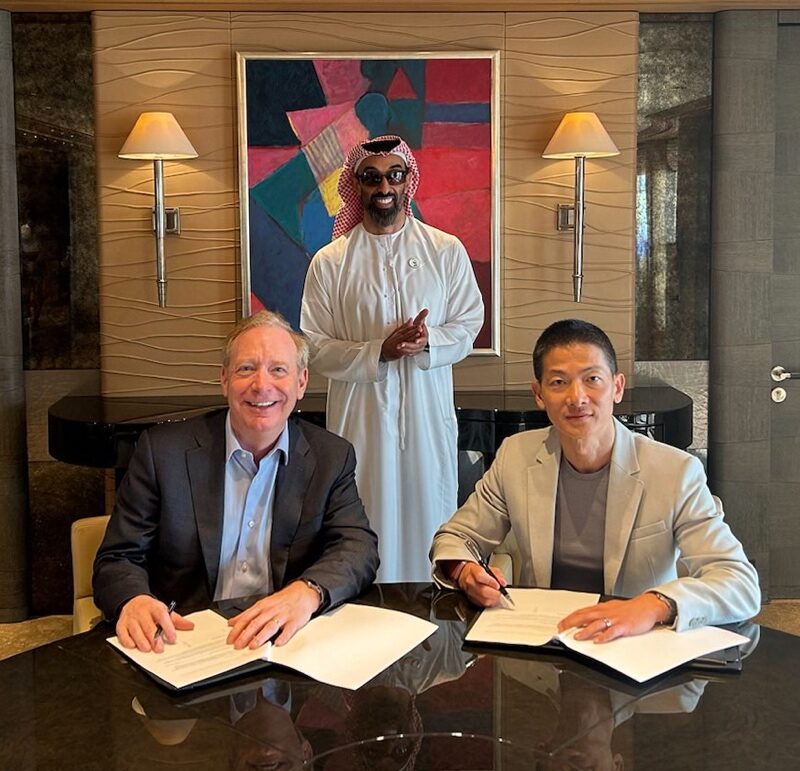

The normalization agreements between Israel and four Arab states in 2020 has also boosted the sector. The newly established UAE-Israel Business Council, which has united more than 6,000 Emirati and Israel businesspeople, is predicting that bilateral trade could reach $2 billion in 2022, an increase of over 50% from 2021 and many of the newly formed ties are in the tech sector.

“I’ve been working in Israeli high-tech for 25 years and two decades ago would never have dreamt that we would reach where we are today,” said Bin, former president and CEO of RAD Communications, a Tel Aviv-based company that manufactures networking equipment.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many businesses and services into the virtual space, actually “stimulated the demand for high-tech,” Bin explained, adding that Israeli companies were quick to adapt to the new environment and the government stepped in to keep investment flowing into the startup sphere.

“There was a digital transformation, and many things that once took place in the physical world had to move to the virtual world, which increased demand,” he told JI. “The Israeli DNA has the ability to be flexible and to adapt quickly to changing circumstances, also there is a long history of entrepreneurs, investors and government policies that benefit the sector.”

“When [COVID] started, the market went into shock; many investors were reluctant to invest because the uncertainty was high,” Bin explained. “We got money from the government and, for a short while, invested in different types of startups until investors were ready to return — this was one of the main reasons we did not see a fall in the number of startups in the country.”

Established in 2016, the Israel Innovation Authority has three main functions — investing in research and development of innovative and ground-breaking products with an annual investment budget of NIS 2 billion ($640,000); preparing for future technology trends; and enabling regulation, including removing obstacles and finding ways to expand human capital for the high-tech sector.

After the “bumper” year, Bin said he expects the industry to keep growing and expanding, with an emphasis on maintaining Israel’s high-tech inside the country, in contrast to the past, and diversifying into new areas of innovation.

“There has been a paradigm shift that will change many things going forward,” he said. “Traditionally, Israel’s start-up ecosystem was based on the establishment of small companies whose goal was to find a multinational or American company to buy it out.”

Now, Bin said, there are around 10-15 companies that have become giants in their space and are choosing to remain in Israel. He estimates that a further 100 Israeli companies have the potential to become leaders in one of the global markets.

Bin also said that Israel’s high-tech market was beginning to branch out in new directions.

“If Israel was strong in cyber and fintech or the enterprise software market in the past, we have seen a shift into new markets like food-tech, specifically alternative proteins, agritech, and Bio-Convergence (developing new medicine and medical devices),” he said. “The imagination can keep on working here full-time to find many more exciting new things.”

In order to further facilitate the growth, IIA has been working to ease Israeli bureaucracy, loosening regulations in order to allow Israeli companies to flourish. Bin gives the example of the drone market, a focus in recent years for the authority. Bringing together Israeli regulators, the Israeli Aviation Authority and industry innovators, he said, was already “defining the playground so that all parties could benefit from it.”

He also said IIA has invested in one of Israeli high-tech’s biggest challenges — the shortage of manpower. “We intervened in this about two years ago and started implementing new models of recruiting manpower to enter the industry,” said Bin, describing a program for re-training for those with academic qualifications and another to bring in underrepresented populations such as women (who make up roughly 30% of the sector’s employees), Arabs and the ultra-Orthodox.

Bin said there was no single element to Israel’s success in creating a booming global innovation hub. “What you need to create this magic is for it all to happen in the right place at the right time,” he told JI.

Citing a combination of Israel’s risk-taking culture, the country’s necessity to develop defense systems and a very smart government policy, Bin added: “There is also the fact that Israel is so small, and being small is an advantage when it comes to innovation, which often evolves in dense places where everyone knows everyone,” he said. “All these things have blended together well to create wave after wave of innovation.”

“No matter how you want to look at the Israeli ecosystem, whether its capital raised, quality of capital, unicorns, IPOs, whatever metric you want to look at, the Israeli tech ecosystem grew exponentially in 2021, it was our best year yet by far,” concurred Hillel Fuld a tech columnist and startup advisor.

Explaining the growth, Fuld referred to last week’s Torah portion, where it talks about the Jews in Egypt and how the more they were oppressed, the more they multiplied.

“We have this tendency as Jews to thrive under pressure,” he said. “There is an inverse correlation between terror and innovation, meaning you would think that if there is more terror there would be less innovation but that is not the case at all, so in 2021, the year of a pandemic, you would think it would be slow or there would be a decrease in innovation but in reality, that was not the case.”

“To say I was surprised, I was not surprised because all indications showed that we were going to keep growing but the rate of growth did surprise me because it was just so explosive this year,” said Fuld.