Noah’s Ark mosaic puts ancient Jordan synagogue on tourist map

As Arab countries from Bahrain to Morocco reconnect with their Jewish communities, church ruins in Jerash hearken back to biblical flood story

Khalil Mazraawi/AFP via Getty Images

Jerash's colonnaded roads and arenas are a major tourism draw for Jordan

JERASH, Jordan – When archeologists first excavated the remnants of a sixth-century church in the ancient city of Jerash in 1929, they uncovered a mosaic floor filled with images of gazelles, horses, birds, rabbits, snakes and other creatures that tell the biblical story of Noah’s Ark.

Also revealed by the American-British research team were a seven-branched menorah, a ram’s horn, a palm frond and other Jewish icons that indicated the Byzantine church had been built on the foundations of what was once a synagogue.

The “Synagogue-Church,” as it’s labeled on tourist maps, is located near the Temple of Artemis in the northwest quarter of Jordan’s vast Greco-Roman archeological park in Jerash, about 40 kilometers (28 miles) north of the capital city of Amman. It is one of several historical attractions in Jordan that are popular with Jewish and Christian visitors because of their biblical connections. Others include the town of Madaba, with its mosaic map at St. George’s Church that depicts the Holy Land and ancient Jerusalem; and nearby Mount Nebo, revered as the place where Moses looked out over the land of Canaan before his death.

As Arab countries from Egypt and Morocco to Bahrain reconnect with their Jewish pasts, the subject is still very sensitive in Jordan, where more than half the population has Palestinian roots. Three decades since the Hashemite Kingdom made peace with Israel, efforts to normalize those relations in the style of the Abraham Accords, signed two years ago, are opposed by most Jordanians.

Still, the Jordan-Israel peace treaty that was signed in 1994 has enabled hundreds of thousands of tourists to cross easily between the two countries and visit historical sites such as Jerash, once known as Gerasa. Amid the ruins, visitors can see the agglomeration of ethnicities, customs and faiths that have characterized the region throughout the centuries.

As part of a Hellenistic coalition of cities called the Decapolis, Gerasa was established in the mid-second century BC, during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, a Greek Seleucid king, according to historical evidence. The site’s magnificent colonnaded streets, bathhouses, amphitheaters and hippodrome attest to its development under centuries Greek and Roman rule. The city also bears the influence of the Hasmonean Jewish state to the west, whose King Alexander Jannaeus captured Gerasa in 85 BC, leading to an influx of Jews. Gerasa, which later came under Roman rule in the greater Syrian region, appears in an account by Flavius Josephus, the Roman-Jewish historian, of an attack on the city by Jewish rebels from the kingdom of Judea.

The combination of the historical texts, along with artifacts found at the site that were commonly used by Jews at the time, “shows that a big Jewish community dwelled in the city and was well-integrated,” Rubina Raja, a professor of classical archeology at Denmark’s Aarhus University, told The Circuit. Raja and Achim Lichtenberger, a University of Münster archeologist, are co-directors of the International Northwest Quarter Project, which continues to excavate the site.

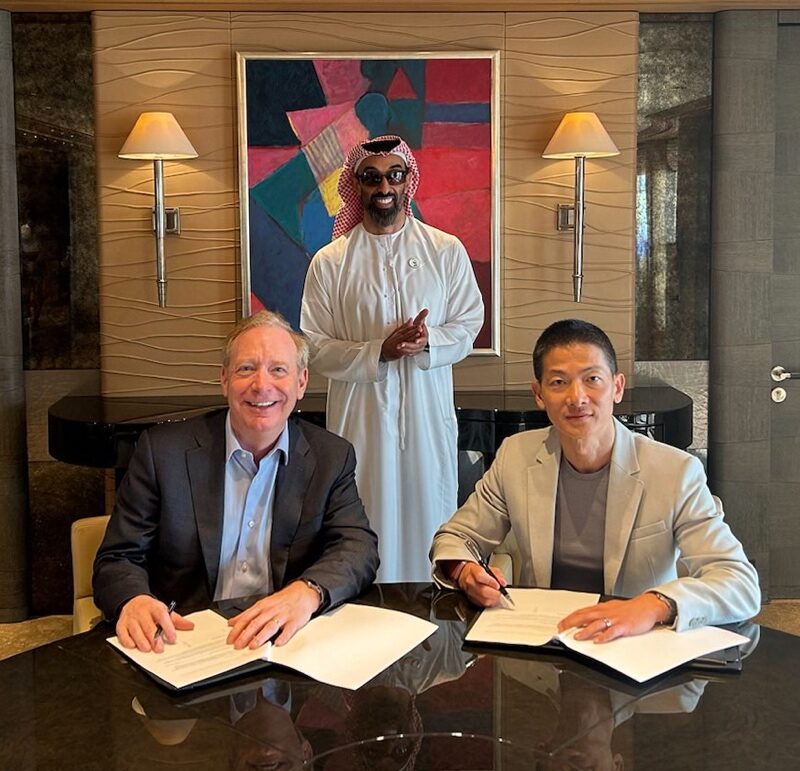

Jerash mosaic floor is filled with images from Noah’s Ark (Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art)

Among the images on the synagogue’s mosaic floor, one of the most striking is a bird perched on a tree branch holding a twig in its beak. It illustrates the verse from Chapter 8 in Genesis, when Noah releases a dove and it returns with an olive leaf, indicating that the floodwaters that covered the earth had receded.

Claudine Dauphin, a British-trained archeologist and longtime researcher of the site, was struck by how clearly the animals are demarcated by category when she described the mosaic in her writings.

“In the upper row are birds; wild and domesticated animals are in the middle row, and impure beasts and rodents are in the lowermost row,” Dauphin, a Senior Member of Somerville College, University of Oxford, told The Circuit. “Two black lines separated the biblical scene of the flood from a wide, predominantly geometric border, which also enclosed animals running from the right and left. Big game pursuing fleeing gazelles on the background of a flower semis, and between the border and the central panel, two birds facing each other and holding in their beaks a vegetal garland.”

Looking at the mosaic’s southern section, she explained, “only the back legs of a wild beast and other animals are visible.” She described a “menorah flanked on the right by a lulav and etrog,” referring to the palm frond and citron fruit that Jews hold during prayers on the festival of Sukkot. The floor also has “an incense shovel or a Torah scroll case, [and] is accompanied by an inscription fitted in between the hind legs of two leaping wild beasts.”

Besides the animals, two of Noah’s sons, Shem and Japheth, are depicted in the mosaic with their names labeled. The Greek inscription reads, “Holy place. Amen. Peace upon the congregation.”

The motif of Noah’s Ark has also been discovered in excavations at other ancient sites in the region including Huqoq in northern Israel and Mopsuestia in Turkey.

When the Gerasa synagogue was first erected has still not been determined conclusively, Dauphin said. “The plan of the synagogue is difficult to exactly determine in view of the alterations made in order to replace the synagogue with the church,” she said. “The synagogue was oriented east-west, thus opposite the orientation of the future church.”

Lichtenberg’s research indicated that the original synagogue was built between the late fourth and early fifth centuries CE. To turn the building into a church, he said, “the former eastern courtyard with the atrium was demolished, and an apse was erected above it,” he said, referring to a semicircular recess with an arched roof.

Why the synagogue was taken over in approximately 530 CE by the Byzantine Christian authorities remains a matter of debate. One theory is that the synagogue was simply abandoned by the Jews. Another is that the Jews were converted en masse to Christianity. The third hypothesis is that Christian authorities took over the synagogue just as they also appropriated mosques and pagan temples.

“The building of the church was part of the policy of confiscation of synagogues by the church and coincided with the peak of expansion of Christianity,” Dauphin said. “The takeover of the synagogue by Christians does not necessarily mean the end of the Jewish community of Gerasa. How long it survived after the Moslem Conquest [in 635 CE] remains unknown,” she said.

In 749 CE, an earthquake destroyed the church, along with many of Jerash’s other ancient structures. It wasn’t until 1925 that archeologists began to excavate the site and uncover the architectural splendor that has made it Jordan’s second-biggest tourist attraction after the ancient Nabatean city of Petra.