Missing pieces to cultural puzzles appear in UAE-Israel library ties

Rare artifacts in Jerusalem of Abu Dhabi’s founding father, Sheikh Zayed bin Khalifa, provide clues for Emirati researchers at National Library

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF ISRAEL

Researcher Clinton Bailey recorded hundreds of hours of oral history from Bedouins in Israel.

Nearly 120 years ago, Hermann Burchardt, a German Jewish explorer, was traveling in the Middle East, talking to Arab leaders and taking photographs.

Among the iconic pictures was what is thought to be the first image of the founding father of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Zayed bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, known as Zayed the First. He was the great-great-grandfather of the current president of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

Although the pictures Burchardt took in Abu Dhabi became famous in the region and reproduced many times, his personal impressions of the people and places he photographed remained a mystery. He and his fellow travelers were murdered in Yemen in 1909 and his journals were assumed to have been lost.

Eventually, via the estate of Eugen Mittwoch, a German scholar of Islamic and Judaic studies, Burchardt’s missing diary — and hundreds of pages of correspondence, notes and official documents, together with numerous photos — all found their way to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem.

It was this material that delighted Hamad Al-Mutairi, director of the Archives Department of the Emirates National Library and Archives (NLA), based in Abu Dhabi, when he and other colleagues visited Israel last summer. For Al-Mutairi, seeing the Burchardt collection in Jerusalem was thrilling, and filled in the blanks for his researchers. “We were able to see details about the kind of food he ate, and the type of traditional hospitality given to him at that time as a traveler in the region.”

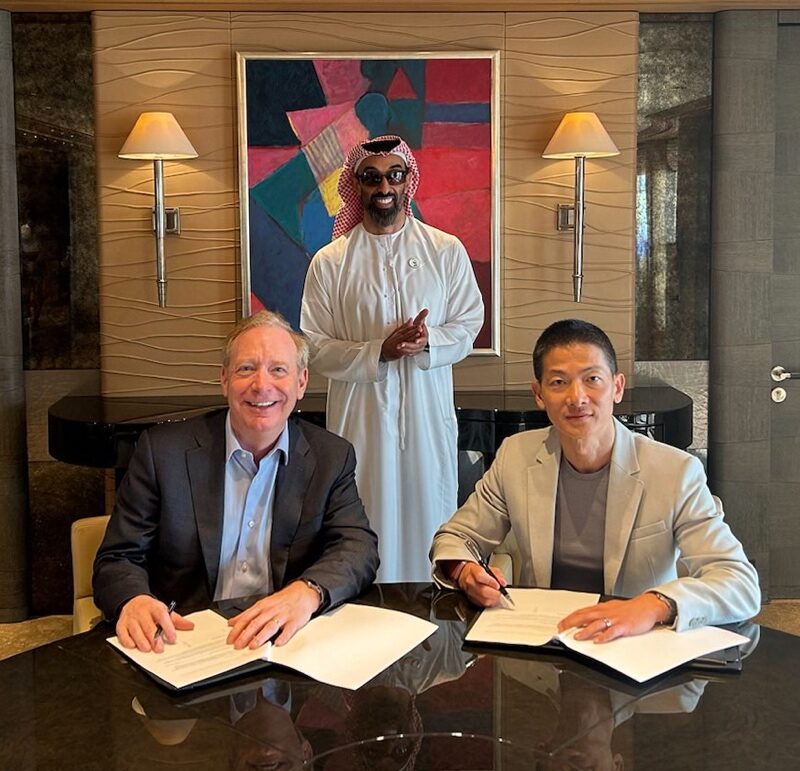

The Emirati visit — and a memorandum of understanding between the two libraries — is a direct and tangible result of the Abraham Accords, signed initially between Israel and three partners — the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco — in 2020.

Libraries and their scholars have an open-handed approach to their research. In general, the libraries are inclined to share as has been the case with Burchardt’s collection, in the early stages of collaboration between Jerusalem and Abu Dhabi. The Burchardt material is essential to drawing a fuller picture of the first years of the individual emirates that now make up the UAE. The Israelis have provided Abu Dhabi with digital copies of Burchardt’s diary and the accompanying papers, which will become part of the NLA collection.

“We didn’t stop there,” said Al-Mutairi. “We’re now trying to find the right time to put together some sort of exhibition about Burchardt, charting his journeys across the region. It might be online or it might be physical.” The formal agreement between the two libraries will ensure that the material will marry the holdings that each has; and in the meantime, experts from the two institutions will work together to enrich and expand background information and metadata related to the archive’s contents, including translations, greatly increasing its value to scholars across the globe as a rare reflection of Gulf history.

It’s difficult to know what expectations each library had of the other, before the Abraham Accords enabled them to work together. But today, what they are both keenest on is developing cooperation, based on their separate expertise.

The UAE has built up an enviable body of material based on oral history, while the Israeli library has tended to focus more on physical collections — its Islam and Middle East collection, for example, includes priceless documents and manuscripts not even found in much of the Arab world.

Samuel Thrope, curator of the Islam and Middle East collection in Jerusalem, said he has been talking with colleagues at the NLA about oral history connected to a project on Clinton Bailey, an American-Israeli researcher who spent 50 years documenting Bedouin culture and society.

The Bailey recordings — all 350 hours of them — are “super-interesting,” said Thrope, and chronicle Bedouin life in the Negev and Sinai between the late 1960s and 2009. They have all been cataloged and digitized — and now we are in the process of transcribing them.”

Bailey was in the desert region in 1967 to conduct a series of now legendary interviews with Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion. Ben-Gurion’s kibbutz, Sde Boker, was surrounded by Bedouin tribes and the curious Bailey, when not talking to the retired politician, began talking to the local Bedouin.

“He talked to them about their daily lives,” said Thrope, “about literature, poetry — there were reciters of poetry, people who had memorized different poems. But the conversations also touched on different topics, of society, law, the oral culture that Bedouin had been expanding and observing for many generations. It’s an amazing primary resource.”

But the team learned that a history heavily reliant on oral traditions had its downsides. “Because Bedouin life has changed so much in the past 50 years, even recordings from 20 or 30 years ago — and certainly recordings from 50 years ago — are almost unintelligible. I’m just learning this now as we work with the transcribers, who are themselves young Bedouin living in the south, often in places where the recordings were made. They tell me that almost every sentence has a word that they just don’t know — because the [present-day] Bedouin don’t use it any more.”

The challenge, said Thrope, “of dealing with a language that even native speakers can’t understand” led his team to ask for help from UAE colleagues. “They have produced a series of books in Arabic, called Their Memory, Our History, based on their work. The written history of the UAE is fairly limited, but the oral history is a hugely important part of the national memory. It’s great to have been able to turn to them, they have been incredibly helpful.”

For Al-Mutairi, the opportunity to work with the Jerusalem team on this oral history project allowed the Abu Dhabi library to demonstrate what it had learned about oral history. The Emiratis realized, he said, that the Jerusalem transcribers were dealing “with Arabic, but in a different dialect than we use in this region.” They sat with their Jerusalem counterparts and told them how they dealt with oral history: “There are some requirements to be identified. For example, the speaker or the storyteller, the location of the interview, some keywords which might be useful later on for the retrieval of the information. And the last part is how to publish the material.”

Al-Mutairi said that various Bedouin tribes had very specific terminology “when dealing with camels, or food, or tools for day-to-day activities.” Some of these words have gone into a glossary in the NLA for use with their oral history material — and now it’s hoped that such a glossary will be made available to Jerusalem.

If the NLA is the senior partner in the oral history project, it’s the other way around when it comes to written material, manuscripts and artworks. As Al-Mutairi explains: “We used to be the National Archives only and recently we became the National Library and Archives. Now, we are concentrating on manuscripts and other such material and it’s something new to us. We are sure we will have so much collaboration in that area.”

The Emiratis are expanding what they do, figuring out their acquisition strategy and putting new buildings up for the library work. In that regard they’ve been holding small online workshops with the NLI — itself moving into a grand new building later this year — about how to make the buildings user-friendly.

Separate from the NLA in the capital city of Abu Dhabi, one of the most distinctive new buildings in the UAE is the new Mohammed bin Rashid Library in Dubai, which opened in June and was designed to look like an open book.

The Abraham Accords, said Al-Mutairi, “have opened the door for collaboration and exchange of knowledge between two very experienced teams.” But the Emiratis did not confine their outreach just to the NLI in Jerusalem. They also signed a memorandum of understanding with Haifa University and to date have held two physical and three online workshops with the Haifa academics. They are discussing the possibility of joint research projects between the two institutions, about the topography and geography of the region.

Al-Mutairi was particularly impressed, during his visit to Haifa, to see that the university students “were working in our platform, Arabian Gulf Digital Archives, or AGDA, and they had created a tool and enhanced it. I was really surprised and really happy; I told them that we need to present this to any international event relating to archives.” In fact, an opportunity is coming up soon, when in October 2023 Abu Dhabi hosts the International Archives Congress, which is expected to attract around 5,000 delegates.

Meanwhile there continues to be a flow of visitors between the two countries. Last month, said Al-Mutairi, a delegation of Israelis taking part in a technology conference in Abu Dhabi made a side visit to the NLA. “It’s said that the new oil is data — and we have the data,” he said with a laugh. “The Israelis wanted to know what technology we were using” — specifically, what steps the Emiratis were taking to make the data they are presently collecting, future-proof.

The NLA is exploring new ways of data preservation, updating continuously, conscious that they may run out of physical storage room. One such system is called “PIQL film,” which could allow material to be kept for 2,000 years. The possibilities are being shared with the Israelis.

Both Al-Mutairi and Thrope are clearly excited by the opportunities presented in sharing ideas. “To have the wall break down between our collection and the Arab world through the auspices of the UAE — that’s just great. I would love people from all over the region to benefit from the collections we have, to use them, to study them,” Thrope said. “Having this relationship with Abu Dhabi and Dubai just makes that possible.”