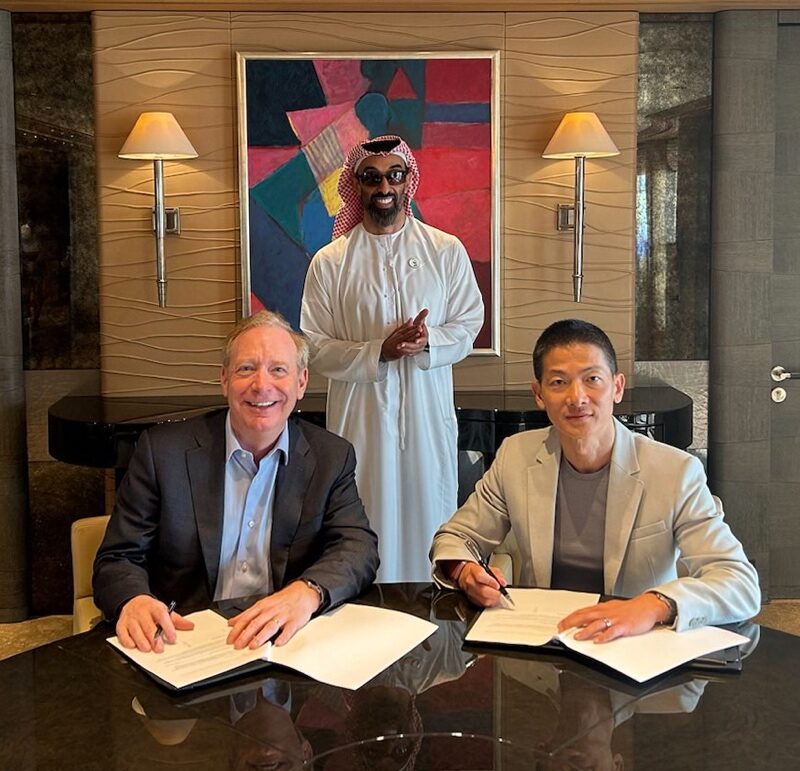

Mohamed Abdel Hamid/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Ukraine deal narrowly averts grain crisis across North Africa

Egypt's dependence on imports from Ukraine and Russia is fueling concerns in Gulf about threat to regional stability

WASHINGTON, D.C. — As ships loaded with wheat and corn finally departed from the Black Sea port of Odesa last week, it appeared the world had dodged yet another humanitarian crisis in North Africa.

Whether the grain deal arranged after weeks of complex negotiations involving Russia, Ukraine and Turkey will hold remains to be seen. What’s clear, though, is the role Ukraine and Russia have played through their exports in preventing civil disruption in capitals from Cairo to Tripoli.

“Egypt has probably been affected directly by this war in Ukraine more than any country in the region,” Motaz Zahran, Egypt’s ambassador to the United States, said in an interview, pointing to food shortages that shook past governments. “We consider ourselves among the victims.”

The two warring countries have until now supplied 80% of Egypt’s wheat imports — 50% from Russia and 30% from Ukraine — as well as 40% of its tourist traffic. The fighting brought both to a halt, trapping some 20 million tons of grain inside Ukraine, with virtually no room to store it all.

Gulf is Watching

Middle East risk manager Ghanem Nuseibeh said the Gulf states — particularly Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar — will do whatever they can to help Egypt, such as financing grain imports, because they fear a repeat of the popular insurrections from 2010 known as the Arab Spring that spread through the region and were touched off, in part, by food shortages and rising food prices.

“Egypt’s stability is paramount to the Gulf and the rest of the region,” Nuseibeh, founder of London-based Cornerstone Global Associates, told The Circuit.

David Beasley, executive director of the United Nations World Food Program, said that even before the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the situation in Africa was dire, given all that preceded it: COVID-19, ethnic war in Ethiopia, the crisis in Afghanistan and worsening drought across the continent. Then came Ukraine — “a nation that grows enough food to feed 400 million people — from the breadbasket of the world to now the longest bread lines of the world,” he said at a July 19 forum with the Council on Foreign Relations.

“It’s going to get much worse,” warned Beasley, whose agency before the war typically sourced half the wheat, barley, corn and other grains purchased for distribution worldwide from Ukraine. “What we were seeing in 2021 has unfolded now to be exacerbated or put on steroids because of the Ukrainian situation.”

The repercussions are also being felt in Tunisia, where food scarcity was among the problems that sparked the Arab Spring. “This war shows us just how dependent we are,” Hanéne Tajouri Bessoussi, Tunisia’s newly installed ambassador in Washington, said in an interview. “Before this, no one was aware of the importance of this country in Europe — even though the war is far from us.”

Recalling Arab Spring

It was Tunisia, after all, where on Dec. 18, 2010, a young fruit vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest police corruption and mistreatment, sparking a wave of unrest in part because of food shortages that quickly spread to Algeria, Jordan, Egypt and Yemen. Within months, Tunisian strongman Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had fled to Saudi Arabia and Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak had resigned after 30 years in power. Civil wars in Libya, Syria and Yemen endure to this day, all stemming from the unrest triggered by the original protests.

And today, climate change, extreme drought and supply chain disruptions resulting from the pandemic have exacerbated food shortages throughout North Africa and the Middle East, adding a dangerous element to the already unstable mix.

In April, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates pledged up to $22 billion to shore up Egypt’s economy, mindful that weak finances and food scarcity can undermine political stability throughout the Arab world.

Tajouri Bessoussi, who took up her post last December — only two months before Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered the invasion of his smaller neighbor — said more than 60% of her country’s wheat supply comes from Russia and Ukraine.

“The economic situation in Tunisia is very bad,” she said. “It was further aggravated by the COVID pandemic, and now the war in Ukraine. The current government is trying to implement essential reforms to put Tunisia back on the path of growth and prosperity, and for that, we are now negotiating with the IMF,” she noted, referring to the International Monetary Fund.

Skyrocketing Prices

Zahran, Egypt’s ambassador, said that despite the steep decline in tourism — a mainstay of Egypt’s economy — gross domestic product grew more than 3 percent a year during the pandemic. This year, GDP was projected to grow by 5.7%, but that was before Russia’s invasion sent food prices skyrocketing. On top of that, Egypt saw a slowdown in the passage of vessels through the Suez Canal, which generates a significant part of its budget, Zahran said.

Egypt joined 140 other nations in condemning Russia for invading Ukraine. The resolution passed the U.N. General Assembly 141-5, with 35 countries abstaining. “That vote in itself reflects Egypt’s principled positions despite the fact that its impacts on the economy are horrible,” Zahran said. “It’s a matter of principle.”

Egypt has not, however, downgraded its relations with Moscow or prevented Russian vessels from transiting the Suez Canal.

Before the Ukraine war broke out, Egypt’s government under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi scrambled to find other sources of grain, said Mirette Mabrouk, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Middle East Institute.

“At the beginning, they said they had about nine months’ supply of wheat,” Mabrouk said in a July 15 webinar. “The problem is that wheat goes into making bread, and bread is highly subsidized in Egypt.”

Bread Subsidies Matter

In fact, after Egypt received an IMF loan in 2016, it embarked on a very aggressive reform program that involved slashing or removing most subsidies. The only one left untouched was the bread subsidy, to which two-thirds of Egyptians are entitled.

“That bread can very often make the difference between you going to bed hungry or not,” said Mabrouk, noting that 29.6% of Egypt’s people live below the poverty line. “It’s so sensitive that the price of subsidized bread in Egypt hasn’t changed in 35 years. The last time they tried to raise prices, in 1977, it touched off two years of rioting.”

Michael Brodsky, Israel’s ambassador to Ukraine, said he remains deeply concerned. “This war in Ukraine is affecting the Middle East very badly,” Brodsky said in a phone interview. “We should remember that rising food prices were among the biggest reasons for the Arab Spring, so this is potentially very dangerous.”

The grain deal signed July 23 in Istanbul and brokered by the U.N. and Turkey was especially tricky, requiring attention not just to the sensitivities of Russia and Ukraine, but also to those of Turkish President Recip Tayyip Erdogan, Nuseibeh said.

“Turkey is trying to benefit politically from this, and as long as the Turkish intervention helps reduce risks of hunger,” Nuseibeh said, “the region will welcome this with the proviso that it does not come at a steep political cost.”