KDT

Koch’s Israeli investment chief aims to disrupt venture capital funding

Eli Groner was a top aide to Netanyahu before joining U.S. firm that has given nearly $1 billion to Israeli startups

Eli Groner meets with hundreds of startups each year as the managing director in Israel for Koch Disruptive Technologies, which since 2018 has doled out almost $1 billion to emerging Israeli companies. For the fraction of those deemed disruptive enough to get funding, KDT, the venture arm of gigantic U.S. conglomerate Koch Industries, sees itself as a devoted ally that doesn’t expect quick returns.

“We are patient capital,” Groner told The Circuit during an interview at the firm’s 35th -floor Tel Aviv office overlooking the Mediterranean. “We invest with the expectation that we are going to partner with them forever or for at least for 10 years. Now, that is not always the case, but that is certainly the way we look at it when we make an investment. So, we want to work with people that are high integrity, resilient, committed and playing the long game.”

Dressed in a light-blue button-down shirt and tailored tan trousers, the American-born Groner has business experience and an insider government background that impressed KDT when the firm opened its Israel office three years ago, the only one outside the United States. Now 52, he spent three years as a top aide to then-Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, serving as director-general of the Prime Minister’s Office. Any political savvy he gained in government has been useful in representing Koch Industries, whose owners are among the biggest contributors to right-wing causes in the U.S.

KDT, founded in 2017, focuses on “early and growth stage” technology companies around the world, with an aim also at finding synergies to boost parent company Koch Industries. The Wichita, Kan.-based conglomerate had revenue last year of more than $125 billion and 120,000 workers worldwide. It owns a diverse group of companies involved in activities that include manufacturing, agriculture, paper, building materials, oil refining, renewable energy and medical products.

KDT’s first foray in Israeli startups, and first investment ever, preceded Groner’s joining the firm – $100 million in backing for Insightec, a maker of magnetic resonance-guided ultrasound technology. The company’s products help alleviate ailments like Essential Tremor, which causes involuntary trembling of the head, hand and voice, and Parkinson’s disease, which causes uncontrolled movements throughout the body. KDT followed up with an additional $100 million to the company in March 2020.

When it first funded Insightec, KDT didn’t have an office in Israel. On a visit to meet industry players, company executives had an encounter with Groner, fresh out of the Prime Minister’s Office, who offered a geopolitical overview of Israel and the region. “We really connected on vision and values,” Groner said. “Six months later I got a formal offer to join KDT and open up the Israel office.”

Groner has since led KDT’s investments in 13 Israeli startups that operate in fields ranging from health care, semiconductors and cybersecurity to manufacturing and agriculture.

As a rule, Koch-funded companies must be “disruptive” — having the potential to promote “creative destruction — the continuous process of iterating, improving and destroying current business models and platforms, even our own,” the firm says on its website. Ideally, they can also transform Koch Industries, to help the mother ship keep up with industry developments and best prepare itself for the future. As far as the chosen entrepreneurs, they must be dedicated and flexible, Groner said.

“You can have the best vision, the best strategy, the best technology, [and] you’re going to be beaten down time and again, because things aren’t always going to go your way,” he said. “A founder who is resilient, who can roll with the figurative punches, and figure out how to execute, no matter which curveballs are thrown his or her way, those folks are gold.”

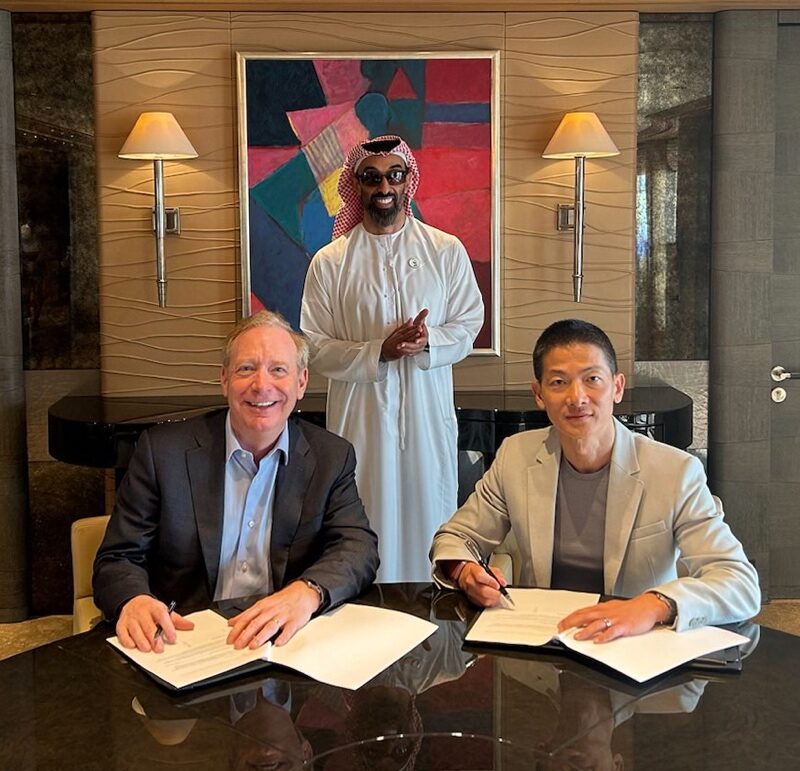

Groner’s efforts come during a period when Israel is forging new partnerships with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and other Arab countries, under the banner of the Abraham Accords signed two years ago.

It is a “very exciting time for the region,” he said. “It is an opportunity for everyone, whether you are an entrepreneur, whether you are an investor. But at the end of the day, it is going to be the same values and principles that apply. Are you aligned in values? Are you aligned on vision?”

Because of Koch’s wide variety of enterprises, the conglomerate can help startups test and sell their technologies within its holding companies and its network of partners, thus getting their product to market faster and providing “meaningful support for entrepreneurs,” Groner said.

In the health care sector, besides Insightec, KDT has invested in Immunai, which seeks to map the immune system to create new therapies and drugs, and NeuraLight, which is building a platform driven by artificial intelligence to improve drug development for patients with neurological disorders.

In the semiconductor field, KDT led two investment rounds for a total of $217 million in Vayyar, a developer of radar imaging technology for sensors used in a variety of industries. KDT has also invested in cybersecurity startups Cyrebro, where it led a $40 million funding round, and OneLayer, in which it made an equity investment of $6.5 million; KDT led a $45 million investment round in the drone startup Percepto, and invested in the agtech firm Greeneye Technology, which uses AI and deep learning technologies for the selective spraying of pesticides. KDT’s first exit was the sale of Israeli software firm DeepCube to Nasdaq-traded Nano Dimension Ltd for $70 million, according to Crunchbase data.

According to data compiled by the IVC Research Center, which tracks the Israeli tech industry, capital raised in Israel with Koch participation totaled $1.33 billion in 2021 as opposed to $150 million in 2017. In the first nine months of 2022, capital raised by Israeli startups with Koch participation totaled $304 million.

Corporate venture capital involvement, such as Koch’s, in Israeli tech companies has surged over the past few years, with such deals accounting for almost 50% of the total in 2021, a bonanza year for fundraising by startups. Investment has slowed in 2022,

“The rise in activity by Koch reflects a rise in the involvement of corporate venture capital funds in the Israeli tech ecosystem, and the need of local tech firms for the significant amounts of money they can provide,” said Marianna Shapira, a senior analyst at IVC.

Koch Industries has been the subject of controversy for years – with critics pointing to the extraordinary wealth of members of the Koch family, their large contributions to conservative political causes, and their vast political influence on a variety of issues in the U.S., including skepticism about climate change. OpenSecrets, an organization that tracks campaign spending, reported that Koch Industries has injected over $1 million in backing, directly and indirectly, dozens of House and Senate candidates who voted against certifying Joe Biden’s presidential victory after protesters rioted in the U.S. Capitol.

Asked whether controversy surrounding the Koch family affects his work, Groner said he is sure there are many company founders that his office funds who do not agree with him or with Koch politically. “The best way to change people’s perceptions is to work closely with them and partner with them and focus on areas where we are aligned.”

Declining to address the issue directly, a company spokesperson pointed to an article written two years ago by Charles Koch. In it, the billionaire co-owner, chairman and CEO of Koch Industries congratulated President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris on their victory and called for all parties to work together to solve the crises that are holding back the nation.

On the issue of climate change, the Koch website says “manufacturing and a healthy environment aren’t mutually exclusive” and shows data about how the firm is cutting emissions, producing less waste and investing in energy efficiency projects.

As chief of Netanyahu’s office from June 2015 to May 2018, Groner was responsible for domestic and international policy decisions, from developing Israel’s offshore natural gas fields and deregulating the economy to setting up the nation’s cyber bureau and its digital health policy. At the same time, he juggled foreign policy issues and was tasked to deal with Israeli political parties.

Before joining Netanyahu, Groner was Israel’s economic attaché to Washington. Previously he was a senior advisor to the chairman of Tnuva, one of Israel’s largest food makers. He also worked for six years as a consultant at McKinsey & Company and five years at The Jerusalem Post as a sports and economic reporter.

As a child he lived in the central New York city of Binghamton, where his father was the rabbi of an Orthodox Jewish congregation. After moving to Israel, Groner performed his military service as a paratrooper. He went to college at Israel’s Bar-Ilan University and earned an MBA at New York University.

The business world is different from politics and government, Groner said, but he feels very much at home in both worlds. “It is two different muscles, two different skill sets. And it is very, very hard to succeed in both because it requires different skills. I personally, am very intrigued by both worlds. I enjoy both worlds and recognize that each one has different benefits and drawbacks.”

He must also now operate in an environment that has turned sour for tech, with shares and valuations plunging globally in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rising inflation and lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The lower valuations, Groner said, are healthy for the economy, as they can create investment opportunities while clearing the field of poorly performing companies.

“You are going to see valuations go back to normal, sanity returning to the markets,” he said. “Any great crisis is a horrible thing to waste. This is going to create incredible opportunities for people that are patient and take a long-term view. ”Koch is committed to Israel, he said, because the company has identified that there is within the tiny nation a “very distinctive concentration of disruptive technology.”

Groner said Israel’s value comes from a unique concentration of entrepreneurs, academic institutions, the military, venture capitalists and growth equity investors spread over a small geographical area.

“There’s no place else like it in the world, really,” he said. “That is my focus here.”